Visibility of the thin lunar crescent: the sociology of an astronomical problem (A case study)

By Nidhal Guessoum, Kiram Meziane

In the Islamic calendar, a new month starts the day after the first naked-eye sighting of the thin crescent, shortly after a luni-solar conjunction. The crescent can be observed after sunset in the general western direction. As the visibility depends strongly on the atmospheric conditions, the beginning of the Islamic new month cannot be predicted very precisely. Three times a year, because of religious events, officials of Islamic countries decree the beginning of the month on the basis of reports from witnesses who volunteer to watch the thin crescent. In the present study, we confront the dates as decreed by the officials with the astronomical data and criteria of earliest visibility. The data collection consists of 115 dates corresponding to the religious occasions in Algeria between 1963 and 2000. We have found those dates to be largely inconsistent with the astronomical data. The rate of impossible cases (where the crescent was not present at all in the sky, let alone be visible) is about 17.4%. In more than half the cases, one or more of the absolute limits or all-time records of visibility was/were violated. And according to most or all the prediction criteria of visibility, there were about 80% cases in error. We have also found that the error rates versus time correlate well with the sociological changes that occurred in Algeria between 1963 and 2000. Finally, we should emphasize that comparatively to Algeria, the error rates are higher in the Middle-East. These results suggest that the officials must reconsider their approach in the determination of the beginning of the Islamic months.

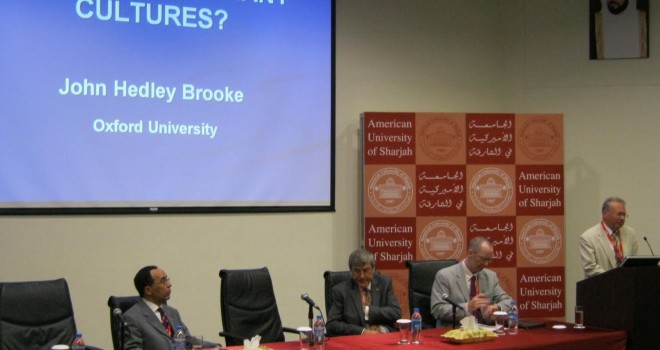

Nidhal Guessoum is associate dean at the American University of Sharjah. He can be followed on Twitter at: www.twitter.com/@NidhalGuessoum

Kiram Meziane, University of New-Brunswick, Physics Department, Canada

Source: http://www.adsabs.harvard.edu/

Download full article here