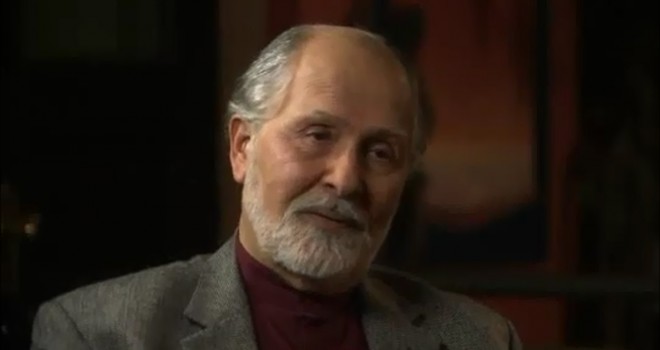

Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1933–) is a master, in every sense of the word, including the intellectual and the Sufi meanings. I have attended some of his class lectures, I have heard him give talks to general audiences, I have watched him being interviewed at length, and I have sat down and talked with him one-on-one in his office a few times. He is mesmerising. Nasr has the look and mannerisms of a spiritual sage, the fluency of thought and speech of a skilled orator, and the rich command of a master academician; indeed, I have never seen Nasr use any notes. Most impressive about him is his calm eversmiling face and his gentle humble dealings. The first time I visited him in his office (at George Washington University, where he holds the chair of Islamic studies), he offered me his bibliographical index, which then (in the mid-nineties) contained a list of no less than 50 books and 400 articles; he autographed it forme with ‘To ProfessorNidhal… ’ Some of his books have been translated to a good half-dozen languages, but – as far as I have been able to check – no more than handful have been translated into Arabic!

And yet I do not subscribe to this philosophy, on the contrary – as will transpire throughout this book.

Seyyed Hossein was born in Iran in 1932, but he was sent to the USA for education at the age of 12; he graduated from high school in 1950 as valedictorian of his class and won the Wyclifte Award for the school’s all-round outstanding accomplishments. He then received a scholarship for physics at MIT, thus becoming the first Iranian undergraduate student at the prestigious university. He was soon attracted to the fields of history and philosophy of science, and to metaphysics and philosophy more generally. It is also in that period that he became familiar with the works of Frithjof Schuon, the famous authority on perennial philosophy, who was to become his spiritual and intellectual master.

He was barely in his mid-twenties when he published two seminal and influential books, An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines, a slightly modified version of his doctoral thesis at Harvard, and Science and Civilization in Islam, which rocked the field of history and philosophy of science by insisting that the nature of science in the Islamic civilization was fundamentally different from the modern one and that one had to review the concept of knowledge and civilization before understanding the enterprise of science through history. Indeed, Nasr’s first book was his Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines; I read it some 20 years ago, and it blew me away, even though I did not understand much of it (then). I have since read it again and read many reviews of it; it is a classic work, and I will be referring to it extensively in the chapter on cosmology.

After his doctorate, Nasr returned to Iran, where he was successively appointed university professor, dean, academic vice-chancellor and then president of Sharif University, and later chancellor of Melli/Beheshti University. During the 1970s, he was asked by the Iranian Emperess to head the Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy, where he was given a chance to revive and implement the principles of the traditional school. That experiment, which saw the participation of illustrious world thinkers of Sufi inclination, like Henri Corbin, Sachiko Murata, William Chittick and Allameh Tabatabaei, ended with the occurrence of the Islamic revolution in Iran. For these reasons, Nasr found himself having to leave Iran for the USA. I remember the sadness on Seyyed Hossein’s face when he told me that his greatest loss was the huge library of personal books he had to leave behind.

To understand Nasr, whom I have elsewhere referred to as a ‘neo-traditionalist’, one must keep in mind that he is in effect a Sufi master. Sufism has been defined by some as both an approach and a special type of knowledge; the Sufi follower seeks to ultimately find God in him, in and by

way of his heart. This inner search, the Sufis insist, leads to the discovery of esoteric truths, a whole world of knowledge. The process by which this search is conducted, individually and in groups, is known as the tariqah (the way/path/method). The tariqah always refers to the Sufi orders, which are schools of Sufi traditions established by Grand Masters (e.g. the Qadiriyyah of Sheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani, the Tijaniyyah of Sheikh Ahmad Tijani etc.) with a particular method for seeking God within the general Sufi tradition. Tariqah is only a way, and it is meant to lead to haqiqah (Ultimate Truth), which is God, or at least the knowledge of Him.

The Sufi philosophy revolves around the following central principle: Existence is one; all phenomena are partial aspects or reflections of Existence or Truth; our senses are subjective, limited and deceiving tools, particularly when they lead us to see/believe in dualistic distinctions between beings, phenomena and experiences. Furthermore, Sufism emphasises the personal experience of things and makes extensive usage of parables, allegories and metaphors in understanding various aspects of Reality and their relations, similarities and interdependences.

Moreover, many have noted the important fact that Sufism transcends classical theological divisions within Islam (Sunism, Shiism etc.); some have seen this Islamic mysticism as being quite similar in its methods and general philosophies with other spiritual traditions such as Zen Buddhism and Gnosticism.

For the past half-century Nasr has remained a major intellectual figure of Islam, recognised as such both in the West and in the Muslim world. Among other honors he has received, one must note that he was the first (of only two so far) Muslim(s) to have been invited to give the prestigious Gifford Lectures (on science and religion), which have been taking place for over a century and have so far received more than 200 illustrious thinkers, each delivering a series of lectures. The lectures he delivered in 1981 were later published as Knowledge and the Sacred, which is considered as one of his most significant books.

Nidhal Guessoum is associate dean at the American University of Sharjah. He can be followed on Twitter at:

www.twitter.com/@NidhalGuessoum.