Science in Arab renaissance

While recent events in the Arab world have focused on political upheaval, the region is now in dire need of a new revolution to reform the cultures of education and research, says Nobel laureate Ahmed Zewail and Sherif Sedky.

In the past few years, an awakening, through the ‘Arab Spring’, has focused on a political dimension of societal change. While the process of transformation begins with democracy, it does not end there. Though public uprisings have brought political changes, a new revolution is needed to transform the culture of learning. The failure of Arab education is a significant underlying cause of youth discontent in the region and has serious cultural, economic and political consequences.

The status of the Arab world in science and education is unacceptable. Its contribution to international scientific research is insignificant and Arab universities do not regularly rank among the world’s 500 best institutions. It is remarkable that between 25 and 40% of the Arab population of 350 million remains illiterate, while adult skills in the digital age are now defined in terms of literacy, numeracy, and problem solving.

In Egypt, which has the largest population of Arab countries, hundreds of thousands of students get a university education that is not compatible with the modern world. And, on the global market, there are no technological products “made in Arabia”.

It is too simplistic to ascribe a single cause, such as a false distinction between faith and reason. From a genetic point of view, Arabs are no different from those of any other ethnicity; there is no geographic monopoly on intelligence. Clearly, Arabs and Muslims in Spain, North Africa, and Arabia were at the apex of civilization when Christian Europe was in the dark ages.

The reasons for this lack of endeavor and achievement are myriad; including colonization, corruption, and constitutional deficiencies restricting human liberty and freedom of thought. And, for decades, the use of religion in politics and politics in religion have clouded national goals and diverted attention from the real issues facing Arab nations.

The question that needs to be answered is not what went wrong, but what can be done now? Revolutionary changes, not incremental ones, have to take place in education and scientific thought, with three essential components for progress.

First is the building of human resources by restoring literacy, ensuring active participation of women in society, and reforming education.

Second, there is a need to reform the national constitution to allow freedom of thought; to streamline and rationalize bureaucracy; to develop merit-based systems and create a credible and enforceable legal code.

Thirdly, and most tangibly, the constitution should ensure that the budget for research and development is above 1% of the nation’s GDP. In light of recent revolutions in Egypt, Tunisia and elsewhere, these changes are possible.

In this vision, human capital is paramount. The Arab world needs to nurture a new generation of professionals capable of thinking critically and creatively, one with contemporary knowledge of science and technology, and with the new emerging disciplines in physical, medical, and social sciences.

Such a pool of knowledge would help identify and provide solutions for fundamental problems facing society. Research into alternative energies, water resources, or drug design can bring numerous social benefits and rewards from the country’s economic growth and the participation in the global market.

Changes must be initiated at the root of the education system which is based on rote learning with a focus on the quantity rather than the quality of information delivered to students. This should be replaced with a merit-based system designed to encourage free and creative thinking, with practical experiences.

The landscape of funding and recognition in research also needs to be reformed. Today’s convention of using the number of publications to determine candidates for academic promotion has proven to be of little value and must be replaced with a framework to identify original and innovative contributions. Finally, there should be a strong link forged between the academic and industrial sectors to maximize potential mutual benefits from basic research and industrial interests, globally and domestically.

“Renaissance in the Arab world will not be possible without genuine government recognition of the critical role of science in development.”

In Egypt, the pioneering National Project for Scientific Renaissance, “Zewail City of Science and Technology”, was set up in 2011 to encompass these concepts in education, research, and the industrial impact. The project is funded by donations from the Egyptian people and the government.

At the heart of the City is the University of Science and Technology, whose primary role is to attract talented students from all over the country and offer unique academic curricula in cutting-edge fields of sciences and engineering.

The second major arm of the project comprises research institutes staffed with world-class scientists prioritizing research into essential national problems. The institutes, equipped with state-of-the-art equipment, represent a wide range of interdisciplinary fields, including nanotechnology, environmental engineering, renewable energy, space and communication technology, materials science, biomedical science, and physics of earth and the universe.

The third and last major component is the “Technology Pyramid”, which is responsible for commuting research output to industrial applications. It is designed to establish, with intellectual property protection, incubators and spin-off companies and to attract major international corporations to encourage a healthy climate for research-industry exchanges.

The benefits from the Zewail City of Science and Technology, domestically and on a world stage, are numerous. We believe this prototype initiative of three structures, if transferred to other parts of the Arab world, will change the landscape of education and scientific research, and, through significant international participation, will foster new opportunities for the youth of Arab nations.

Renaissance in the Arab world will not be possible without genuine government recognition of the critical role of science in development and policies providing commensurate funding for basic research and reform of rigid bureaucracy which thwarts progress.

In doing so, Arab nations will regain confidence to compete in today’s international science and globalised economy. It is gratifying to see several new centres of advanced education and research and development being set up in the region.

However, the goal of the Egyptian initiative is different. Under one umbrella we are providing the milieu for education and research, from school and university stages to advanced manufacturing and market levels. This may be a route to developing society scientifically and culturally, to growing economically, and for restoring the prominent role of Arabs worldwide.

By Ahmed Zewail & Sherif Sedky, published in Nature Middle East, January 9th 2014.

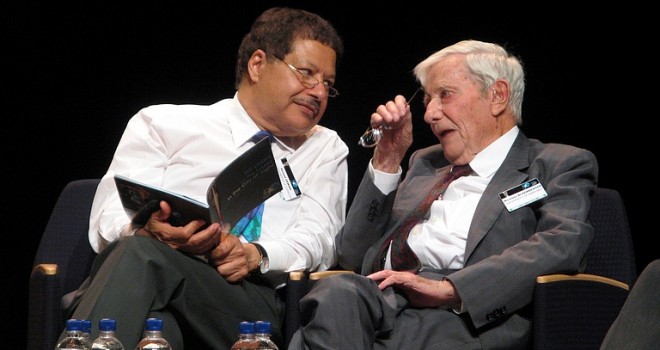

Ahmed Zewail won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He is the Linus Pauling Chair professor of chemistry and professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and is currently the director of the Moore Foundation’s Center for Physical Biology at Caltech. He is also the founding president of the Zewail City of Science and Technology.

Sherif Sedky is the founding provost of Zewail University of Science and Technology and the director of the Nanotechnology Center at Zewail City of Science and Technology.