Close encounters of the Arab kind

Have you ever heard of Alif the Unseen, computer hacker and recipient of an ancient scroll written by mythological spirits?

Or Ajwan, a teenager on an intergalactic quest to save her son from the clutches of those who wish to convert him into a super-warrior?

Probably you haven’t. Possibly you should have. Introducing the rapidly evolving face of Arabic science fiction literature.

Unknown world

It is a genre that at times challenges a political reality in countries where even peaceful protest can be a one-way ticket to a lengthy jail term, while at other times helps to explain the otherwise unimaginable splendour of an almighty God.

Such is its lure that a recent conference held at the Science Museum’s Dana Centre in London was packed with those keen to exchange views on the subject.

Rarely has mainstream sci-fi attempted to grapple with the complexities of the Arab world.

As Lebanese Canadian sci-fi writer Amal el-Mohtar explained, the mainstream sci-fi she grew up with was “very, very white… except for the aliens, of course.”

Though it might at times have featured characters from ethnic minorities, rarely did it seek to positively engage with other cultures beyond exoticisation or fear-mongering.

In fact, “what you tend to get is Western science fiction that is very normative; gender looks remarkably the same and race looks remarkably pale”, said Ms Mohtar.

It might come as a surprise that one of the first sci-fi novels written was not, in fact, Shelley’s Frankenstein or HG Wells’ The Time Machine, but the work of 13th Century Baghdad-based writer and physician, Zakariya al-Qazwini.

Awaj bin Anfaq is the story of a curious alien who arrives on planet Earth to observe human behaviour and finds himself perplexed by the oddities of this apparently sophisticated species.

Neither is Mr Qazwini’s work a regional anomaly.

There are numerous examples of early Islamic sci-fi or fantasy fiction from the Arab world, not least of course, the fabulous Arabian Nights, replete with flying carpets, mystical jinn and even a little intergalactic travel.

The Middle East in Western sci-fi

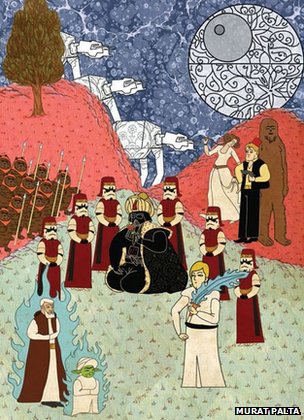

George Lucas used spiritual elements of Islam, along with other world religions, to convey the universal understandings of good and evil in Star Wars. “Al-Jeddi” is an Arabic term meaning master of the mystic-warrior way.

Frank Herbert’s Dune also contains a plethora of Arabic terms of reference as well as being a profound analogy on the struggle for the monopoly of oil between East and West. Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 resonates the predicament of many in the Middle East between Islamist repression or repression of Islamism.

Ray Bradbury had a strong bond to the Middle East, especially to Baghdad, the city his imagination inhabited. He saw himself in the same tradition as the fantasy storytellers of The Thousand and One Nights. In the Illustrated Man, he re-invented Scheherazade’s frame narrative by weaving unrelated short stories together.

Source: Sindbad Sci-Fi

Cultural imperialism

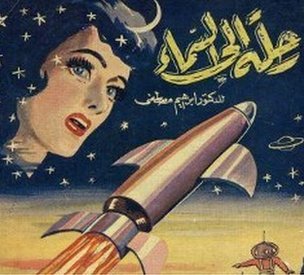

The reasons why this fledgling expedition into new literary territory never fully made lift-off remains, of course, unknown.

But for Pakistani writer and academic Ziauddin Sardar, it has to do with a change of outlook across the region.

As the “golden age” of the Islam drew to a close, so did the optimism and enthusiasm felt by many for the mysteries of the future, he claims.

The Islamic world turned to reflect on its glorious past, and to a certain extent, to the West, whose speed of expansion may well have seemed to be the stuff of sci-fi.

For Ms Mohtar, the cultural imperialism that resulted from this shift still afflicts her home country today.

“While I was living in Lebanon in the 1990s, I read very few fairy tales, or the kinds of stories that nourish a child’s soul, in Arabic. I read them in French and in English.”

“I do feel there’s been a sort of rupture that this legacy of colonialism has left.”

Yet despite the great expanse of time that separates the sci-fi of the 13th Century Islamic world from that of modern Arab writers like Amal el-Mohtar, in Mr Sardar’s opinion, there are certain elements they share.

“I think there are two things you need before you can have science fiction in a society; one is an appreciation of what science is all about, and the second is some awareness of the future,” he said.

The Arab world may not know what the future holds, but it is acutely aware of its existence, hurling the region forward at an unprecedented pace.

The Arab Spring and its continuing aftershocks are a part of that change, but they represent a mere fragment of a much broader upheaval.

As one guest at the conference said: “Having grown up in Egypt, to me we are living in a sci-fi. Thirty years ago we didn’t even have electricity in most of Egypt.”

Self-reflection

Is it just a translation of a Western genre – a hamburger spiced with cardamom and rosemary? Unsurprisingly, the panellists didn’t think so.

For them, Arabic sci-fi is an opportunity to respond to the damaging stereotyping of the “Arab Other” in mainstream sci-fi, as well as a space to explore the complex challenges facing Middle East today.

“The problems of contemporary Islamic society – the problem of gender, the problems with authoritarianism – all of these are explored very thoroughly in Arab sci-fi. But most importantly of all, it is Arabs reflecting on themselves,” said Mr Sardar.

Few would argue that Arab sci-fi literature still has a long way to go before it breaks into the mainstream.

Often it must wrestle with low budget allowances, political restrictions and audiences increasingly accustomed to televised entertainment.

Yet if the buzzing enthusiasm of the sold-out audience at the Dana Centre was anything to go by, Arab sci-fi’s place in the future it seeks to understand seems assured.

Suggested reading

- Alif the Unseen by G Willow Wilson

- Utopia by Ahmed Khaled Tawfik

- Throne of the Crescent Moon by Saladin Ahmed

By Lydia Green, published in BBC Arabic, October 9th 2013.